Dissecting PostgreSQL Data Corruption

| Categories: | PostgreSQL® |

|---|---|

| Tags: | planetpostgres planetpostgresql postgresql 18 |

PostgreSQL 18 made one very important change – data block checksums are now enabled by default for new clusters at cluster initialization time. I already wrote about it in my previous article. I also mentioned that there are still many existing PostgreSQL installations without data checksums enabled, because this was the default in previous versions. In those installations, data corruption can sometimes cause mysterious errors and prevent normal operational functioning. In this post, I want to dissect common PostgreSQL data corruption modes, to show how to diagnose them, and sketch how to recover from them.

Corruption in PostgreSQL relations without data checksums surfaces as low-level errors like “invalid page in block xxx”, transaction ID errors, TOAST chunk inconsistencies, or even backend crashes. Unfortunately, some backup strategies can mask the corruption. If the cluster does not use checksums, then tools like pg_basebackup, which copy data files as they are, cannot perform any validation of data, so corrupted pages can quietly end up in a base backup. If checksums are enabled, pg_basebackup verifies them by default unless –no-verify-checksums is used. In practice, these low-level errors often become visible only when we directly access the corrupted data. Some data is rarely touched, which means corruption often surfaces only during an attempt to run pg_dump — because pg_dump must read all data.

Typical errors include:

-- invalid page in a table: pg_dump: error: query failed: ERROR: invalid page in block 0 of relation base/16384/66427 pg_dump: error: query was: SELECT last_value, is_called FROM public.test_table_bytea_id_seq -- damaged system columns in a tuple: pg_dump: error: Dumping the contents of table "test_table_bytea" failed: PQgetResult() failed. pg_dump: error: Error message from server: ERROR: could not access status of transaction 3353862211 DETAIL: Could not open file "pg_xact/0C7E": No such file or directory. pg_dump: error: The command was: COPY public.test_table_bytea (id, id2, id3, description, data) TO stdout; -- damaged sequence: pg_dump: error: query to get data of sequence "test_table_bytea_id2_seq" returned 0 rows (expected 1) -- memory segmentation fault during pg_dump: pg_dump: error: Dumping the contents of table "test_table_bytea" failed: PQgetCopyData() failed. pg_dump: error: Error message from server: server closed the connection unexpectedly This probably means the server terminated abnormally before or while processing the request. pg_dump: error: The command was: COPY public.test_table_bytea (id, id2, id3, description, data) TO stdout;

Note: in such cases, unfortunately pg_dump exits on the first error and does not continue. But we can use a simple script which, in a loop, reads table names from the database and dumps each table separately into a separate file, with redirection of error messages into a table-specific log file. This way we both back up tables which are still intact and find all corrupted objects.

Understanding errors

The fastest way to make sense of those symptoms is to map them back to which part of an 8 KB heap page is damaged. To be able to test it, I created a “corruption simulator” Python script which can surgically damage specific parts of a data block. Using it we can test common corruption modes. We will see how to diagnose each with pageinspect, look if amcheck can help in these cases, and show how to surgically unblock queries with pg_surgery when a single tuple makes an entire table unreadable.

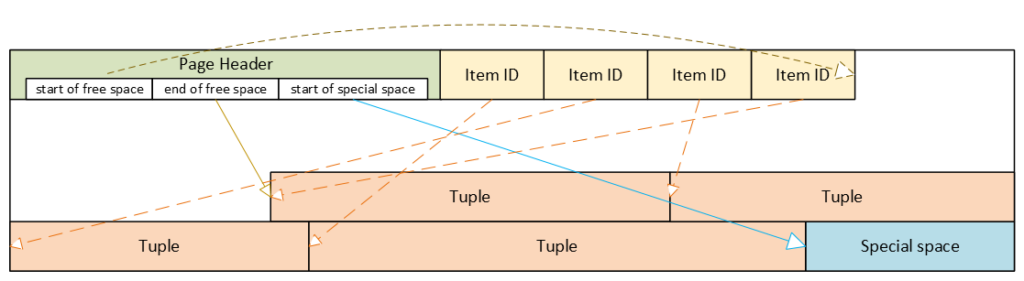

PostgreSQL heap table format

- Header: metadata for block management and integrity

- Item ID (tuple pointer) array: entries pointing to tuples (offset + length + flags)

- Free space

- Tuples: actual row data, each with its own tuple header (system columns)

- Special space: reserved for index-specific or other relation-specific data – heap tables do not use it

Corrupted page header: the whole block becomes inaccessible

The page header contains the layout pointers for the page. The most important fields, which we can also see via pageinspect are:

- pd_flags: header flag bits

- pd_lower: offset to the start of free space

- pd_upper: offset to the end of free space

- pd_special: offset to the start of special space

- plus lsn, checksum, pagesize, version, prune_xid

ERROR: invalid page in block 285 of relation base/16384/29724

This is the only class of corruption error that can be skipped by enabling zero_damaged_pages = on when the cluster does not use data block checksums. With zero_damaged_pages = on, blocks with corrupted headers are “zeroed” in memory and skipped, which literally means the whole content of the block is replaced with zeros. AUTOVACUUM removes zeroed pages, but cannot zero out unscanned pages.

Where the error comes from in PostgreSQL source code

/* * The following checks don't prove the header is correct, only that * it looks sane enough to allow into the buffer pool. Later usage of * the block can still reveal problems, which is why we offer the * checksum option. */ if ((p->pd_flags & ~PD_VALID_FLAG_BITS) == 0 && p->pd_lower <= p->pd_upper && p->pd_upper <= p->pd_special && p->pd_special <= BLCKSZ && p->pd_special == MAXALIGN(p->pd_special)) header_sane = true; if (header_sane && !checksum_failure) return true;

SELECT * FROM page_header(get_raw_page('pg_toast.pg_toast_32840', 100));

lsn | checksum | flags | lower | upper | special | pagesize | version | prune_xid

------------+----------+-------+-------+-------+---------+----------+---------+-----------

0/2B2FCD68 | 0 | 4 | 40 | 64 | 8192 | 8192 | 4 | 0If the header is tested as corrupted, we cannot diagnose anything using SQL. With zero_damaged_pages = off any attempt to read this page ends with an error similar to the example shown above. If we set zero_damaged_pages = on then on the first attempt to read this page everything is replaced with all zeroes, including the header:

SELECT * from page_header(get_raw_page('pg_toast.pg_toast_28740', 578)); WARNING: invalid page in block 578 of relation base/16384/28751; zeroing out page lsn | checksum | flags | lower | upper | special | pagesize | version | prune_xid -----+----------+-------+-------+-------+---------+----------+---------+----------- 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0

Corrupted Item IDs array: offsets and lengths become nonsense

- ERROR: invalid memory alloc request size 18446744073709551594

- DEBUG: server process (PID 76) was terminated by signal 11: Segmentation fault

SELECT lp, lp_off, lp_flags, lp_len, t_xmin, t_xmax, t_field3, t_ctid, t_infomask2, t_infomask, t_hoff, t_bits, t_oid, substr(t_data::text,1,50) as t_data

FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('public.test_table', 7));

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_data

----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+--------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+----------------------------------------------------

1 | 7936 | 1 | 252 | 29475 | 0 | 0 | (7,1) | 5 | 2310 | 24 | | | \x01010000010100000101000018030000486f742073656520

2 | 7696 | 1 | 236 | 29476 | 0 | 0 | (7,2) | 5 | 2310 | 24 | | | \x020100000201000002010000d802000043756c747572616c

3 | 7504 | 1 | 189 | 29477 | 0 | 0 | (7,3) | 5 | 2310 | 24 | | | \x0301000003010000030100001c020000446f6f7220726563

4 | 7368 | 1 | 132 | 29478 | 0 | 0 | (7,4) | 5 | 2310 | 24 | | | \x0401000004010000040100009d4d6f76656d656e74207374

Here we can nicely see the Item IDs array – offsets and lengths. The first tuple is stored at the very end of the data block, therefore it has the biggest offset. Each subsequent tuple is stored closer and closer to the beginning of the page, so offsets are getting smaller. We can also see lengths of tuples, they are all different, because they contain a variable-length text value. We can also see tuples and their system columns, but we will look at them later.

Now, when we damage the Item IDs array and diagnose how it looks like – output is shortened because all other columns are empty as well. Due to the damaged Item IDs array, we cannot properly read tuples. Here we can immediately see the problem – offsets and lengths contain random values, the majority of them exceeding 8192, i.e. pointing well beyond data page boundaries:

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax ----+--------+----------+--------+--------+-------- 1 | 19543 | 1 | 16226 | | 2 | 5585 | 2 | 3798 | | 3 | 25664 | 3 | 15332 | | 4 | 10285 | 2 | 17420 | |

SELECT * FROM verify_heapam('test_table', FALSE, FALSE, 'none', 7, 7); blkno | offnum | attnum | msg -------+--------+--------+--------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 | 1 | | line pointer to page offset 19543 is not maximally aligned 7 | 2 | | line pointer redirection to item at offset 5585 exceeds maximum offset 4 7 | 4 | | line pointer redirection to item at offset 10285 exceeds maximum offset 4

Corrupted tuples: system columns can break scans

- 58P01 – could not access status of transaction 3047172894

- XX000 – MultiXactId 1074710815 has not been created yet — apparent wraparound

- WARNING: Concurrent insert in progress within table “test_table”

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid ----+--------+----------+--------+------------+------------+------------+--------------------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+------- 1 | 6160 | 1 | 2032 | 1491852297 | 287039843 | 491133876 | (3637106980,61186) | 50867 | 46441 | 124 | | 2 | 4128 | 1 | 2032 | 3846288155 | 3344221045 | 2002219688 | (2496224126,65391) | 34913 | 32266 | 82 | | 3 | 2096 | 1 | 2032 | 1209990178 | 1861759146 | 2010821376 | (426538995,32644) | 23049 | 2764 | 215 | |

- XX000 – unexpected chunk number -556107646 (expected 20) for toast value 29611 in pg_toast_29580

- XX000 – found toasted toast chunk for toast value 29707 in pg_toast_29580

Dealing with corrupted tuples using pg_surgery

Even a single corrupted tuple can prevent selects from the entire table. Corruption in xmin, xmax and hint bits will cause a query to fail because the MVCC mechanism will be unable to determine visibility of these damaged tuples. Without data block checksums, we cannot easily zero out such damaged pages, since their header already passed the “sanity” test. We would have to do salvaging row-by-row using a PL/pgSQL script. But if a table is huge and the count of damaged tuples is small, this will be highly impractical.

In such a case, we should think about using the pg_surgery extension to freeze or remove corrupted tuples. But first, the correct identification of damaged tuples is critical, and second, the extension exists since PostgreSQL 14, it is not available in older versions. Its functions require ctid, but we must construct a proper value based on page number and ordinal number of the tuple in the page, we cannot use a damaged ctid from tuple header as shown above.

Freeze vs kill

Frozen tuples are visible to all transactions and stop blocking reads. But they still contain corrupted data: queries will return garbage. Therefore, just freezing corrupted tuples will most likely not help us, and we must kill damaged tuples. But freezing them first might be helpful for making sure we are targeting the proper tuples. Freezing simply means that function heap_force_freeze (with the proper ctid) will replace t_xmin with value 2 (frozen tuple), t_xmax with 0 and will repair t_ctid.

But all other values will stay as they are, i.e. still damaged. Using the pageinspect extension as shown above will confirm we work with a proper tuple. After this check, we can kill damaged tuples using the heap_force_kill function with the same parameters. This function will rewrite the pointer in the Item ID array for this specific tuple and mark it as dead.

Warning — functions in pg_surgery are considered unsafe by definition, so use them with caution. You can call them from SQL like any other function, but they are not MVCC-transactional operations. Their actions are irreversible – ROLLBACK cannot “undo” a freeze or kill, because these functions directly modify a heap page in shared buffers and WAL-log the change. Therefore, we should first test them on a copy of that specific table (if possible) or on some test table. Killing the tuple can also cause inconsistency in indexes, because the tuple does not exist anymore, but it could be referenced in some index. They write changes into the WAL log; therefore, the change will be replicated to standbys.

Summary

| Categories: | PostgreSQL® |

|---|---|

| Tags: | planetpostgres planetpostgresql postgresql 18 |