This week version 1.3 of our PostgreSQL® appliance Elephant Shed was released.

The highlight of the new version is support for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 and CentOS 7. As is already the case for Debian, the appliance heavily relies on the postgresql-common infrastructure which was previously ported to RPM.

The well-known PostgreSQL® RPM packages from yum.postgresql.org are integrated into the system via pg_createcluster and can be administrated from the Elephant Shed web interface.

All other Elephant Shed components like pgAdmin4, Grafana, Prometheus, pgbackrest, Cockpit or shellinabox work in the same way as in the Debian version of the appliance. Only the SELinux functionality has to be deactivated in order to run pgAdmin4 and shellinabox as their packages do not support this.

Besides the port to RPM the appliance infrastructure was updated. The Prometheus node-exporter is now available in version 0.16 in which many metric names were adjusted to the Prometheus naming scheme. The Grafana dashboard was updated accordingly. The Apache configuration was switched from authnz_pam to authnz_external as the former is not available on CentOS and stable functionality could not longer be guaranteed on Debian Buster.

The next items on the Elephant-Shed roadmap are the integration of the REST-API in order to control particular components, as well as multi-host support so that several Elephant-Shed instances can be controlled simultaneously.

An overhaul of the user interface is planned as well.

The updated packages are available for download at packages.credativ.com. If Elephant-Shed was installed already, the updates are provided via apt as usual.

The open-source PostgreSQL® appliance Elephant-Shed is developed by credativ and is increasingly popular, as the most important compontents for the administration of PostgreSQL® servers are already included. Adjustments and extensions can be done at any time.

Comprehensible technical support for Elephant-Shed is offered by credativ including guaranteed service-level agreements and optional 365 days and 24/7 hours.

Today PostgreSQL® version 11 was released. The new release brings improvements in many areas.

Since version 9.6 query plans can be executed on multiple CPU cores in parallel, this is now supported for other plan types, especially the creation of B-tree indexes. Sequential scans and UNION queries have also been improved.

Brand new is the possibility to optimize queries via Just-in-Time Compilation (JIT). When PostgreSQL® is compiled, the source code is stored as LLVM bit code. When executing a query whose planner cost exceeds a limit, libllvm then translates this bit code into native machine code specifically for that query. Since all used data types etc. are known in advance, the machine code eliminates all case distinctions that are generally necessary. The feature is disabled by default and can be enabled with “SET jit = on;”. In PostgreSQL® 12 it should then be active by default.

Until now only functions could be defined on SQL level. New are now procedures which can manage BEGIN/COMMIT independently. Batch operations can now be completely transferred to the database side.

Table Partitioning section has been further improved to support hash partitioning. Integration with partitions using postgres_fdw has also been improved. It is now possible to create a default partition that holds data that does not fall into any of the existing partitions.

This Amp goes to 11!

Other improvements include the ability to add columns with default values to tables without having to rewrite the table completely. “Covering Indexes” allows more index accesses than “Index Only Scan”. Window functions now also support the RANGE and GROUPS keywords.

More information can be found in the release announcement of the PostgreSQL® project.

Next week the PGConf.EU will take place in Lisbon. We from credativ are present with a booth and celebrate the PostgreSQL® release with our “This Amp goes to 11” T-shirt.

The shirt is available for free at our booth. If you don’t attend the conference, you can order a shirt. The profits will be donated to the PostgreSQL® project.

The second beta release of PostgreSQL 11 (which is now feature frozen) has been released recently. Time to look at some of the improvements that credativ has contributed in the area of checksums and backups.

Checksum verification during base backups

Since version 9.3 it is possible to enable checksums for the underlying storage of tables and indices during instance creation. Those checksums raise SQL errors if bit errors are encountered in their respective data pages, which allows for early discovery of storage issues. However those checksums are only verified if queries access the corrupted page. Running an explicit check is only possible with the forthcoming pg_verify_checksums application from version 11, however, it requires an offline instance in order to work.

Our change allows for verification of checksums during base backups. This is a good opportunity to verify the checksum consistency as all data blocks needs to be read during a base backup anyway. Checksum failures are logged as warnings (rather than errors) in order not to abort the whole base backup when they occur. The commonly used pg_basebackup application was extended with the –no-verify-checksums option which disables the verification.

Replication slots during base backups

The second change concerns the handling of replication slots by pg_basebackup during the setup of standby servers. Replication slots allow a primary to reserve the required transaction logs for the standby associated with the slot, even if it is temporarily down. Previous releases already allowed using a replication slot with pg_basebackup, however, this slot had to be created manually beforehand. Our change adds the new option -C or –create-slot and allows the on-shot creation of a standby clone including the usage of replication slots:

$ pg_basebackup -v -h primary.lan -D data --slot=standby1 --create-slot --write-recovery-conf

pg_basebackup: initiating base backup, waiting for checkpoint to complete

pg_basebackup: checkpoint completed

pg_basebackup: write-ahead log start point: 0/1D000028 on timeline 1

pg_basebackup: starting background WAL receiver

pg_basebackup: created replication slot "standby1"

pg_basebackup: write-ahead log end point: 0/1D0000F8

pg_basebackup: waiting for background process to finish streaming ...

pg_basebackup: base backup completed

$ cat data2/recovery.conf

standby_mode = 'on'

primary_conninfo = 'user=postgres passfile=''/var/lib/postgresql/.pgpass'' host=primary.lan

port=5432 sslmode=prefer sslcompression=1 krbsrvname=postgres target_session_attrs=any'

primary_slot_name = 'standby1'

Afterwards the standby just has to be started and will replicate automatically.

In addition, several other small improvements to pg_basebackup and its testsuite were done by us.

Parallel dump to /dev/null

A patch that did not make it into the release is presented here nevertheless: parallel pg_dump to /dev/null in the directory format. The reason for it is the common usage of pg_dump to check for errors in a PostgreSQL instance where /dev/null/ is used a target in order not to use additional disk space. The problem is that /dev/null can only be used in the custom format which does not allow dumping in parallel. The directory format supports multiple concurrent processes but cannot use /dev/null as target as it is not a directory. Our patch adds support for /dev/null as a target when using the directory format.

The reasons for the rejection were not technical issues with the patch but the fact that pg_dump is not a diagnostics tool and no special support for that should be included. Nevertheless, the submitted patch works and is being used by our clients. Versions of the patch for PostgreSQL 9.3, 9.4, 9.5, 9.6 and 10 are available.

The credativ PostgreSQL® Competence Center has released a project roadmap for the PostgreSQL® Appliance Elephant Shed.

Elephant Shed is a freely available PostgreSQL® solution developed by credativ, which combines management, monitoring and administration into one system.

The project roadmap for 2018 includes following points:

- Q2 2018: Support for Ubuntu 18.04

- Q3 2018: Support for CentOS 7

An additional planned feature is the implementation of REST API to control individual components. REST stands for REpresentational State Transfer and is an application programming interface based on the behavior of the World Wide Web. Specifically the PostgreSQL® database and the backup via pgBackRest should be addressed.

Multi host support is also planned. A central control of several Elephant Shed instances is thus possible.

In order to make Elephant Shed even more user friendly, various configuration parameters of the web interface are going to be adjusted.

The project roadmap is of course also constantly being worked on. On GitHub you can leave us your feedback at any time.

We would like to take this opportunity to thank all users and testers, and look forward to further development of the project!

For further information please visit elephant-shed.io and GitHub.

This article was originally written by Philip Haas

Elephant Shed is now available as a Vagrant box. This makes it very easy to test and try out the PostgreSQL® appliance.

Vagrant is an Open Source tool for creating portable virtual software environments. By being fully script controlled Vagrant makes it easy to generate virtual machines, in which a software component is installed for testing purposes. Vagrant itself is only the manager, whereas various backends such as Virtualbox or cloud providers can be used for the actual virtualization.

For the development of Elephant Shed we have relied on Vagrant from the very beginning. This “box” is now also available in the Vagrant Cloud.

To use this box Vagrant and VirtualBox must be installed. The host operating system hereby is irrelevant (Linux/MacOS/Windows), but inside the box runs Debian Stretch. The box is then automatically downloaded.

vagrant init credativ/elephant-shed vagrant up

This creates a virtual machine where Elephant Shed runs in a VirtualBox on your computer.

- Default-User:

admin - Default-Passwort:

admin - The web interface listens to port 4433:https://localhost:4433

- PostgreSQL® listens to port 55432:

psql -h localhost -p 55432 -U admin

We are looking forward to your feedback!

Further information can be found on our Elephant Shed project page and on Github as well.

At the beginning of 2018, issues with memory management and Intel processors became public. According to these reports, it is apparently possible to read arbitrary areas of the kernel and userspace memory regions and thus potentially gain access to sensitive areas.

Over the past few days, there have been rumors and speculations about the direction of these developments; meanwhile, there is an official statement from the hackers at Project Zero (Google) who summarize the findings.

What exactly happened?

Essentially, attack vectors were identified that can extract privileged information from the CPU cache, despite a lack of authorization, by leveraging unsuccessful speculative code execution on a processor and precise timing. In doing so, it is possible, despite the lack of authorization (whether from user or kernel space), to read memory areas and interpret their contents. This theoretically enables widespread entry points for malware, such as spying on sensitive data or abusing permissions. These are referred to as Side Channel Attacks. According to current knowledge, not only Intel CPUs (which were initially exclusively assumed to be affected) are impacted, but also AMD CPUs, ARM, and POWER8 and 9 processors.

What is currently happening?

Project Zero summarizes the main issues in the report. Several exploits exist that use different approaches to read privileged memory areas, thereby unauthorizedly accessing information in sensitive areas of the kernel or other processes. Since almost all modern CPUs support speculative execution of instructions to prevent their execution units from idling and thus avoid associated high latencies, a large number of systems are theoretically affected. Another starting point for this attack scenario is the way user and kernel space memory areas interact in current systems. In fact, these memory areas have not truly been separated until now; instead, access to these areas is secured by a special bit. The advantage of this lack of separation is particularly significant when, for example, frequent switching between user and kernel space is required.

The individual attack scenarios are:

- Spectre

This attack scenario utilizes the branch prediction present in modern CPUs, i.e., a preliminary analysis of the probability that certain code or branches can be executed successfully. Here, the CPU is tricked into speculatively executing code that was not actually considered by the prediction. This attack can then be used to execute malicious code. This attack theoretically works on all CPUs with corresponding branch prediction, but according to Project Zero, it is difficult to summarize which processors are affected and in what way. Spectre primarily targets applications in user space. Since Spectre primarily works when faulty code is already present in relevant applications, particular attention should be paid to corresponding updates.

- Meltdown

With Meltdown, speculative execution is used to execute code that cannot actually be reached definitively. These are exception instructions with subsequent instructions that would never be executed. However, due to the CPU’s speculative execution, these instructions are still considered by the CPU. Although there are no side effects from this type of execution, the memory addresses occupied by the instruction remain in the CPU’s cache and can be used from there to test all memory addresses. Since the memory areas of the kernel and user space are currently organized contiguously, not only the entire memory area of the kernel but also all processes running on the system can be read. A detailed description of how the attack works can be found

Both scenarios exploit the respective security vulnerabilities in different ways. The CVEs for the vulnerabilities are:

What happens next?

To prevent Meltdown attacks, corresponding updates are already available for Linux, Windows, and OSX (the latter has contained corresponding changes for quite some time). Essentially, these updates completely separate memory management for kernel and user space (known in Linux as KPTI patches, Kernel Page Table Isolation, formerly also KAISER). This makes it no longer possible to access kernel memory areas from an unprivileged context through privilege escalation on Intel processors. RedHat, as well as CentOS and Fedora, already provide these with updated kernels.

Meltdown attacks, in particular, are effectively suppressed by this; however, for Spectre attacks themselves, based on the current situation, there are no reliable, effective measures. It is important, however, that eBPF and the corresponding execution of BPF code in the Linux kernel are deactivated.

sysctl -a | grep net.core.bpf_jit_enable

sysctl net.core.bpf_jit_enable=0

The change requires “root” permissions.

Performance of Updated Kernels

Due to the separation of memory management for kernel and user space, context switches and system calls become more expensive. This leads to significantly higher latencies, especially if the application causes many context switches (e.g., network communication). The performance losses here are difficult to quantify, as not every workload truly relies on identical access patterns. For critical systems, load tests on identical test systems are therefore recommended if possible. If not possible, the load parameters should be carefully monitored after updating the system. A general performance loss of around 5% is assumed, but tests by kernel developers have also observed losses of up to 30%. Since Page Table Isolation (so far) is only available for x86_64 architectures, these figures only apply to machines with Intel processors. In fact, KPTI is not enabled by default for AMD by the kernel upstream.

Whether KPTI is enabled can be determined via the kernel log:

dmesg -T | grep "page tables isolation"

[Fr Jan 5 10:10:16 2018] Kernel/User page tables isolation: enabled

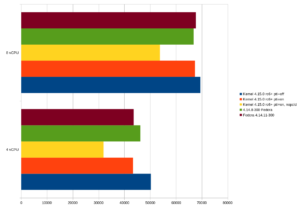

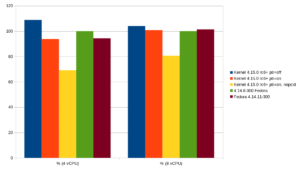

Database users, in particular, are sensitive here, as systems like PostgreSQL® typically cause a high number of context switches under heavy load. At credativ, we classified the impact on a small virtualized system. The basis is a Fedora 27 system as a KVM guest with 4 GByte RAM and fast NVMe storage. However, this plays a rather insignificant role in this test, as the database tests performed with pgbench only have a size of just under 750 MByte. The shared buffer pool of the PostgreSQL® instance was configured with 1 GByte so that the entire database fits into the database cache. The tests were performed with 4 and 8 virtual processors, respectively. The host system has an Intel Core i7-6770HQ processor.

The greatest impact is observed when PCID is not present or is deactivated in the kernel. PCID is an optimization that prevents a flush of the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) when a context switch occurs. Virtual memory addresses are only successfully resolved via TLB if the PCID matches the current thread on the respective CPU. PCID is available from kernel 4.14. The test compares a development kernel with Page Table Isolation (PTI) 4.15.0-rc6, current Fedora upstream kernels with and without security patches. PTI can be deactivated by defining a corresponding argument to the kernel via pti=off during boot.

The Fedora test system already has a very recent kernel (4.14). The difference between the old upstream kernel 4.14.8 without security-relevant patches and the new kernel 4.14.11 is approximately 6%. pgbench then provides the following throughput rates (transactions per second):

If the former standard kernel 4.14.8 of Fedora 27 is taken as 100%, the following results are obtained:

The PostgreSQL® community has also already conducted smaller tests to measure the impact. The results align with our findings. The new kernel 4.14.11 with the relevant patches offers approximately the same performance as the development kernel 4.15.0-rc6 on this platform. In these test cases, 4.14.11 even partially outperforms the old upstream kernel (8 vCPU, comparison 4.14.8, green and 4.14.11, brown). However, the advantage here is just over 1%, so it can be assumed that there are no significant speed differences in this test setup.

For those interested, there is also a dedicated page on the topic. This summarizes all essential information. Also recommended is the summary by journalist Hanno Böck on GitHub, which provides a very good list of all patches for Meltdown and Spectre.

This article was originally written by Bernd Helmle.

The pgAudit extension allows for fine-grained auditing of access to a PostgreSQL® database. Among other things, it is an important component of the recently published

While PostgreSQL® offers configurable logging by itself, the audit messages generated by pgAudit go significantly further and also cover most compliance guidelines. They are also written to the PostgreSQL® log, but in a uniform format and, in contrast to conventional logging via e.g. log_statement, they are deterministic and comprehensive on the one hand, and targeted on the other. For example, it was previously possible to log executed SELECT commands to detect unwanted access to a specific table, but since this then applies to all SELECT commands, it is not manageable in practice. With pgAudit’s so-called object audit logging, it is possible to write only access to specific tables to the audit log by assigning appropriate permissions to an auditor role, e.g.:

Prepare Database

CREATE ROLE AUDITOR; SET pgaudit.role = 'auditor'; CREATE TABLE account ( id INT, name TEXT, password TEXT, description TEXT ); GRANT SELECT (password) ON public.account TO auditor;

Abfragen, die die Spalte password betreffen (und nur solche) erscheinen nun im Audit-Log:

SELECT id, name FROM account; SELECT password FROM account; AUDIT: OBJECT,1,1,READ,SELECT,TABLE,public.account,SELECT password FROM account

Log content

The first field is either SESSION or OBJECT for the corresponding audit logging type. The two subsequent fields are statement IDs, the fourth field is the query class (READ, WRITE, ROLE, DDL, etc.), followed by the command type and (if applicable) the object type and name; the last field is finally the command actually executed. Crucial for auditing is that the commands actually executed are logged, so that circumvention through deliberate obfuscation is not possible. An example of this from the pgAudit documentation is:

AUDIT: SESSION,1,1,FUNCTION,DO,,,"DO $$ BEGIN EXECUTE 'CREATE TABLE import' || 'ant_table (id INT)'; END $$;" AUDIT: SESSION,1,2,DDL,CREATE TABLE,TABLE,public.important_table,CREATE TABLE important_table (id INT)

As can be seen from the command used (lines 1-4), an attempt is made here to prevent the table name important_table from appearing in the log file, but pgAudit reliably logs the table name (field 7) as well as the actually executed CREATE TABLE statement. However, in the case of the conventional PostgreSQL® log, this attempt is successful; only the entered command is logged here:

LOG: statement: DO $$ BEGIN EXECUTE 'CREATE TABLE import' || 'ant_table (id INT)'; END $$;

The pgAudit extension can, in principle, be used from PostgreSQL® version 9.5 onwards. While the version 1.1 of pgAudit packaged by us officially only supports 9.6, the created Debian package can also be used with 9.5 thanks to an additional patch. Therefore, packages for both 9.6 and 9.5 are available on apt.postgresql.org for all supported Debian and Ubuntu versions.

See also:

An interesting tool for quality assurance of C compilers is Csmith, a generator of random C programs.

I had come to appreciate it during the development of an optimization phase for a C compiler. This compiler features extensive regression tests, and the correctness of the translated programs is also tested using standardized benchmarks. The latter, for example, had uncovered a bug in my optimization because a chess program included in the benchmark collection, which was compiled with the compiler, made a different move than expected when playing against itself.

Eventually, however, these resources were exhausted, and everything seemed ready for delivery. I then remembered Csmith, which I had rather scoffed at until that point. “It can’t hurt to run it once.” To my surprise, it found further critical bugs in my code that had not been revealed by the other tests.

When my professional path led back to databases, I missed such a tool for PostgreSQL® development. One year and 269 commits later, I can now announce the first release of SQLsmith 1.0.

SQLsmith generates random SQL queries, taking into account all tables, data types, and functions present in the database. Due to their randomness, the queries are often structured significantly differently than one would write them “by hand” and therefore uncover many edge cases in the Optimizer and Executor in PostgreSQL® that would otherwise never be tested.

Already during development, SQLsmith has found 30 bugs in PostgreSQL®, which were promptly corrected by the PostgreSQL® community.

Anyone who programs extensions for PostgreSQL®, or generally develops for PostgreSQL®, now has an additional debugging tool available with SQLsmith. Users also benefit from SQLsmith through the additional quality assurance that now takes place during PostgreSQL® development.

The source code for SQLsmith is available under GPLv3 on GitHub.

This article was originally authored by Andreas Seltenreich.

Since PostgreSQL® 9.1, PostgreSQL® has implemented an interface for accessing external data sources. The interface defined in the SQL Standard (SQL/MED) allows transparent access to and manipulation of external data sources in the same manner as with PostgreSQL®-native tables. External data sources appear as tables in the respective database and can be used without restriction in SQL statements. Access is implemented via a so-called Foreign Data Wrapper (FDW), which forms the interface between PostgreSQL® and the external data source. The FDW is also responsible for mapping data types or non-relational data sources to the table structure accordingly. This also enables the connection of non-relational data sources such as Hadoop, Redis, among others. An overview of some available Foreign Data Wrappers can be found in the PostgreSQL® Wiki.

Informix FDW

In the context of many Informix migrations, credativ GmbH developed a Foreign Data Wrapper (FDW) for Informix databases. This supports migration, as well as the integration of PostgreSQL® into existing Informix installations, to facilitate data exchange and processing. The Informix FDW supports all PostgreSQL

Installation

The installation requires at least an existing IBM CSDK for Informix. The CSDK can be obtained directly via

% wget 'https://github.com/credativ/informix_fdw/archive/REL0_2_1.tar.gz' % tar -xzf REL0_2_1.tar.gz

Subsequently, the FDW can be built by specifying the CSDK installation folder:

% export INFORMIXDIR=/opt/IBM/informix % export PATH=$INFORMIXDIR/bin:$PATH % PG_CONFIG=/usr/pgsql-9.3/bin/pg_config make

In the listing, the environment variable PG_CONFIG was explicitly set to the PostgreSQL® 9.3 installation. This refers to an installation of PGDG-RPM packages on CentOS 6, where

% PG_CONFIG=/usr/pgsql-9.3/bin/pg_config make install

This installs all necessary libraries. For these to function correctly and for the required Informix libraries to be found when loading into the PostgreSQL® instance, the latter must still be configured in the system’s dynamic linker. Based on the previously mentioned CentOS 6 platform, this is most easily done via an additional configuration file in /etc/ld.so.conf.d (this requires root privileges in this case!):

% vim /etc/ld.so.conf.d/informix.conf

This file should contain the paths to the required Informix libraries:

/opt/IBM/informix/lib /opt/IBM/informix/lib/esql

Subsequently, the dynamic linker’s cache must be refreshed:

% ldconfig

The Informix FDW installation should now be ready for use.

Configuration

To use the Informix FDW in a database, the FDW must be loaded into the respective database. The FDW is a so-called EXTENSION, and these are loaded with the CREATE EXTENSION command:

#= CREATE EXTENSION informix_fdw; CREATE EXTENSION

To connect an Informix database via the Informix FDW, one first needs a definition of how the external data source should be accessed. For this, a definition is created with the CREATE SERVER command, containing the information required by the Informix FDW. It should be noted that the options passed to a SERVER directive depend on the respective FDW. For the Informix FDW, at least the following parameters are required:

- informixdir – CSDK installation directory

- informixserver – Name of the server connection configured via the Informix CSDK (see Informix documentation, or $INFORMIXDIR/etc/sqlhosts for details)

The SERVER definition is then created as follows:

=# CREATE SERVER centosifx_tcp FOREIGN DATA WRAPPER informix_fdw OPTIONS(informixdir '/opt/IBM/informix', informixserver 'ol_informix1210');

The informixserver variable is the instance name of the Informix instance; here, one simply needs to follow the specifications of the Informix installation. The next step now creates a so-called Usermapping, with which a PostgreSQL® role (or user) is bound to the Informix access data. If this role is logged in to the PostgreSQL® server, it automatically uses the specified login information via the Usermapping to log in to the Informix server centosifx_tcp.

=# CREATE USER MAPPING FOR bernd SERVER centosifx_tcp OPTIONS(username 'informix', password 'informix')

Here too, the parameters specified in the OPTIONS directive depend on the respective FDW. Now, so-called Foreign Tables can be created to integrate Informix tables. In the following example, a simple relation with street names from the Informix server ol_informix1210 is integrated into the PostgreSQL

CREATE TABLE osm_roads(id bigint primary key, name varchar(255), highway varchar(32), area varchar(10));

The definition in PostgreSQL® should be analogous; if data types cannot be converted, an error will be thrown when creating the Foreign Table. When converting string types such as varchar, it is also important that a corresponding target conversion is defined when creating the Foreign Table. The Informix FDW therefore requires the following parameters when creating a Foreign Table:

- client_locale – Client locale (should be identical to the server encoding of the PostgreSQL® instance)

- db_locale – Database server locale

- table or query – The table or SQL query on which the Foreign Table is based. A Foreign Table based on a query cannot execute modifying SQL operations.

#= CREATE FOREIGN TABLE osm_roads(id bigint, name varchar(255), highway varchar(32), area varchar(10)) SERVER centosifx_tcp OPTIONS(table 'osm_roads', database 'kettle', client_locale 'en_US.utf8', db_locale 'en_US.819');

If you are unsure what the default locale of the PostgreSQL ® database looks like, you can most easily display it via SQL:

=# SELECT name, setting FROM pg_settings WHERE name IN ('lc_ctype', 'lc_collate');

name | setting

------------+------------

lc_collate | en_US.utf8

lc_ctype | en_US.utf8

(2 rows)

The locale and encoding settings should definitely be chosen to be as consistent as possible. If all settings have been chosen correctly, the data of the osm_roads table can be accessed directly via PostgreSQL®:

=# SELECT id, name FROM osm_roads WHERE name = 'Albert-Einstein-Straße'; id | name ------+------------------------ 1002 | Albert-Einstein-Straße (1 row)

Depending on the number of tuples in the Foreign Table, selection can take a significant amount of time, as with incompatible WHERE clauses, the entire data set must first be transmitted to the PostgreSQL® server via a full table scan. However, the Informix FDW supports Predicate Pushdown under certain conditions. This refers to the ability to transmit parts of the WHERE condition that concern the Foreign Table to the remote server and apply the filter condition there. This saves the transmission of inherently useless tuples, as they would be filtered out on the PostgreSQL® server anyway. The above example looks like this in the execution plan:

#= EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, VERBOSE) SELECT id, name FROM osm_roads WHERE name = 'Albert-Einstein-Straße'; QUERY PLAN ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Foreign Scan on public.osm_roads (cost=2925.00..3481.13 rows=55613 width=24) (actual time=85.726..4324.341 rows=1 loops=1) Output: id, name Filter: ((osm_roads.name)::text = 'Albert-Einstein-Straße'::text) Rows Removed by Filter: 55612 Informix costs: 2925.00 Informix query: SELECT *, rowid FROM osm_roads Total runtime: 4325.351 ms

The Filter display in this execution plan shows that a total of 55612 tuples were filtered out, and ultimately only a single tuple was returned because it met the filter condition. The problem here lies in the implicit cast that PostgreSQL® applies in the WHERE condition to the string column name. Current versions of the Informix FDW do not yet account for this. However, predicates can be transmitted to the Foreign Server if they correspond to integer types, for example:

#= EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, VERBOSE) SELECT id, name FROM osm_roads WHERE id = 1002; QUERY PLAN -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Foreign Scan on public.osm_roads (cost=2925.00..2980.61 rows=5561 width=40) (actual time=15.849..16.410 rows=1 loops=1) Output: id, name Filter: (osm_roads.id = 1002) Informix costs: 2925.00 Informix query: SELECT *, rowid FROM osm_roads WHERE (id = 1002) Total runtime: 17.145 ms (6 rows)

Data Modification

With PostgreSQL® 9.3, the Informix FDW also supports manipulating (UPDATE), deleting (DELETE), and inserting (INSERT) data into the Foreign Table. Furthermore, transactions initiated in the PostgreSQL

=# BEGIN; BEGIN *=# INSERT INTO osm_roads(id, name, highway) VALUES(55614, 'Hans-Mustermann-Straße', 'no'); INSERT 0 1 *=# SAVEPOINT A; SAVEPOINT *=# UPDATE osm_roads SET area = 'Nordrhein-Westfalen' WHERE id = 55614; ERROR: value too long for type character varying(10) !=# ROLLBACK TO A; ROLLBACK *=# UPDATE osm_roads SET area = 'NRW' WHERE id = 55614; UPDATE 1 *=# COMMIT; COMMIT =# SELECT * FROM osm_roads WHERE id = 55614; id | name | highway | area -------+------------------------+---------+------ 55614 | Hans-Mustermann-Straße | no | NRW (1 row)

The example first creates a new record after starting a transaction. Subsequently, a SAVEPOINT is set to secure the current state of this transaction. In the next step, the new record is modified because the locality of the new record was forgotten to be specified. However, since only country codes are allowed, this fails due to the excessive length of the new identifier, and the transaction becomes invalid. Via the SAVEPOINT, the transaction is rolled back to the last created savepoint, and the Informix FDW also implicitly rolls back to this SAVEPOINT on the Foreign Server. Subsequently, the correct country code can be entered within this transaction. After the COMMIT, the Informix FDW also confirms the transaction on the Foreign Server, and the record has been correctly entered.

Summary

Foreign Data Wrappers are a very powerful and flexible tool for integrating PostgreSQL® into heterogeneous database landscapes. These interfaces are by no means limited to purely relational data sources. Furthermore, with the support of modifying SQL queries (DML), the FDW API also enables the integration of writable data sources into PostgreSQL® databases.

This article was originally written by Bernd Helmle.

PostgreSQL® 9.3 is here! The new major version brings many improvements and new functions. This article introduces some of the interesting innovations.

Improved Locking with Foreign Keys

Foreign keys are indispensable for the referential integrity of the data. However, up to and including PostgreSQL® 9.2, these also caused locking problems under certain conditions when UPDATE was performed on columns with foreign keys. Especially with overlapping updates of several transactions via a foreign key, deadlocks can even occur. The following example is problematic in PostgreSQL® 9.2, exemplified by this simple data model:

CREATE TABLE parent(id integer, value text); ALTER TABLE parent ADD PRIMARY KEY(id); CREATE TABLE child(id integer, parent_id integer REFERENCES parent(id), value text); INSERT INTO parent VALUES(1, 'bob'); INSERT INTO parent VALUES(2, 'andrea');

Two transactions, called Session 1 and Session 2, are started simultaneously in the database:

Session 1

BEGIN; INSERT INTO child VALUES(1, 1, 'abcdef'); UPDATE parent SET value = 'thomas' WHERE id = 1;

Session 2

BEGIN; INSERT INTO child VALUES(2, 1, 'ghijkl'); UPDATE parent SET value = 'thomas' WHERE id = 1;

Session 1 and Session 2 both execute the INSERT successfully, but the UPDATE blocks in Session 1 because the INSERT in Session 2 holds a so-called SHARE LOCK on the tuple with the foreign key. This conflicts with the lock that the UPDATE wants to have on the foreign key. Now Session 2 tries to execute its UPDATE, but this in turn creates a conflict with the UPDATE from Session 1; A deadlock has occurred and is automatically resolved in PostgreSQL

ERROR: deadlock detected DETAIL: Process 88059 waits for ExclusiveLock on tuple (0,1) of relation 1144033 of database 1029038; blocked by process 88031. Process 88031 waits for ShareLock on transaction 791327; blocked by process 88059.

In PostgreSQL® 9.3, there is now a significantly refined locking mechanism for updates on rows and tables with foreign keys, which alleviates the problem mentioned. Here, tuples that do not represent a targeted UPDATE to a foreign key (i.e. the value of a foreign key is not changed) are locked with a weaker lock (FOR NO KEY UPDATE). For the simple checking of a foreign key, PostgreSQL® also uses the new FOR KEY SHARE lock, which does not conflict with it. In the example shown, this prevents a deadlock; the UPDATE in Session 1 is executed first, and the conflicting UPDATE in Session 2 must wait until Session 1 successfully confirms or rolls back the transaction.

Parallel pg_dump

With the new command line option -j, pg_dump has the ability to back up tables and their data in parallel. This function can significantly speed up a dump of very large databases, as tables can be backed up simultaneously. This only works with the Directory output format (-Fd) of pg_dump. These dumps can then also be restored simultaneously with multiple restore processes using pg_restore.

Updatable Foreign Data Wrapper and postgres_fdw

With PostgreSQL® 9.3, the API for Foreign Data Wrapper (FDW) for DML commands has been extended. This enables the implementation of updatable FDW modules. At the same time, the Foreign Data Wrapper for PostgreSQL

Event Trigger

A feature that users have been requesting for some time are Event Trigger for DDL (Data Definition Language) operations, such as ALTER TABLE or CREATE TABLE. This enables automatic reactions to certain events via DDL, such as logging certain actions. Currently, actions for ddl_command_start, sql_drop and ddl_command_end are supported. Trigger functions can be created with C or PL/PgSQL. The following example for sql_drop, for example, prevents the deletion of tables:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION del_event_func() RETURNS event_trigger AS $$

DECLARE

v_item record;

BEGIN

FOR v_item IN SELECT * FROM pg_event_trigger_dropped_objects()

LOOP

RAISE EXCEPTION 'deletion of object %.% forbidden', v_item.schema_name, v_item.object_name;

END LOOP;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

CREATE EVENT TRIGGER delete_table_obj ON sql_drop WHEN tag IN ('drop table') EXECUTE PROCEDURE del_event_func();

DROP TABLE child ;

FEHLER: deletion of object public.child forbiddenChecksums in tables

With PostgreSQL® 9.3, it is now possible in environments in which the reliability of the storage solutions used cannot be guaranteed (for example, certain cloud environments) to initialize the database cluster with checksums. PostgreSQL® organizes tuples in blocks that are 8KB in size by default. These form the smallest unit with which the database works on the storage system. Checksums now provide these blocks with additional information in order to detect storage errors such as corrupt block headers or tuple headers at an early stage. Checksums cannot be activated subsequently, but require the initialization of the physical database directory with initdb and the new command line parameter –data-checksums. This then applies to all database objects such as tables or indexes and has an impact on the speed.

Materialized Views

The new PostgreSQL® version 9.3 now also contains a basic implementation for Materialized Views. Normal views in PostgreSQL

These are just a few examples from the long list of innovations that have found their way into the new PostgreSQL® version. With JSON, improvements in streaming replication and some improvements in the configuration such as shared memory usage, many other new features have been added. For those who are interested in detailed explanations of all the new features, the

This article was originally written by Bernd Helmle.

Also worth reading: PostgreSQL Foreign Data Wrapper for Informix